I Walked There

By Sean Watkin

I Walked There was shortlisted for the Bristol Short Story Prize 2015. You can purchase a copy of the Bristol Short Story Prize anthology volume 12 here.

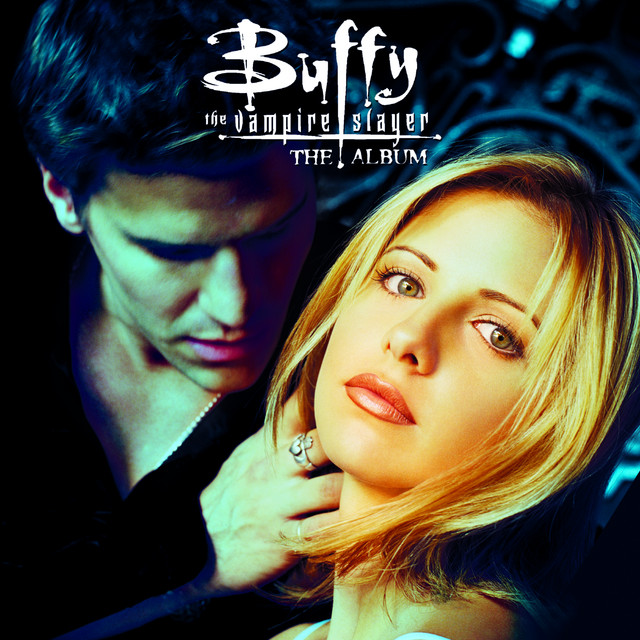

I walked there. It was six miles and to me then it seemed like nothing; like a walk anyone would do for someone who was interested in them. It was a walk Buffy would do for Angel. The sunken arches of my feed throbbed, and November howled over bald fields empty of animals and crops. The season’s rake fingers almost tore through the cream-coloured fleece Nan had given to me. I wore it that night over a plain white t-shirt with matching Diadora trousers, which had pockets half way down the legs. My Nike trainers were beaten and old and rubbed my socks thin as I walked. The kids at school would have called them pasties. I thought I looked good. Cute even.

I’d charged up my mp3 player when I got home from school and marched hard to the Buffy the Vampire Slayer soundtrack. The graffitied walls and fences gave way to hedges and finally to moss covered walls of the older houses that weren’t made of orange bricks.

I was to turn right at the ‘Welcome to Maghull’ sign, which advised all to drive carefully. I’d have to go past the council houses, round the back of Ashworth Hospital, onto the country roads at the back of the town. This was the fifth time we’d met, and I smiled the whole way. We’d not met in the day time yet.

Before I met up with him, I always knocked on for Vicky. Her estate was greener than ours. Lawns separated blocks of houses, littered with crisp packets and cans of Coke. The houses were made from brown brick and dark wood, which made them look nice from the outside. Her windows were filthy, something my mum would never allow to happen at ours.

‘Scrub your windows and wash your nets.’ She’d sing to a tune only she knew. ‘Hoover your carpets and change your beds.’

Vicky pulled open the door with a stained blue and white chequered tea towel over her left shoulder and her chubby baby brother on her right hip. She wore faded black bottoms from an old Bon Bleu tracksuit which were spotted white and pink from bleach, with a green strappy vest. Half-circles had settled under her eyes in first year, and they’d not disappeared since.

‘Oh hiya.’ She stepped out. Closed the door slightly behind her, just enough so the lock didn’t catch.

‘Wanna walk down the farm with me?’

‘I can’t tonight, mate.’ She rolled her eyes toward the baby who stared at me with bright pink cheeks and eyes the colour of penny’s found at the bottom of Nan’s purse. ‘Me mum’s out.’

‘Shall I text you after?’

She nodded. ‘Be careful won’t you?’

I snorted. ‘Well I’m not gonna…’

She laughed. ‘Piss off, that’s not what I meant. Just look after yourself. Text me when you’re there.’

‘Do I look alright?’

‘You look lovely.’ She didn’t look me up and down at all. ‘I’m sorry, I’ve got the tea on. I’ll have to get in.’

I half-hugged her so I didn’t touch the baby and heard the door close as soon as I’d turned my back.

I made it to the country roads quickly from Vicky’s and waited near the farm. Horses moved beyond the wooden fence, black bulking shadow puppets against a purple night sky. Witnessing.

John walked under the yellow lamp lights further up the road. He had this hunched walk. Stiff. Like he expected someone to jump out on him. I walked faster and we met in the twilight between two lampposts.

‘Okay?’ He had bright blue eyes. I couldn’t see them here, just a strip of yellow shine as he looked over my face. He took hold of my hands. ‘You’re freezing, Ste. Where’s your gloves?’

‘I don’t need gloves.’ That was a lie. I’d asked for some on my birthday two weeks ago, but they never got bought. Gloves were the last things my family worried about buying me.

He sighed. ‘Wait by Windemere.’ He turned and walked back on himself.

I crossed the road to an estate of posh houses. The grass in their gardens had no dandelions or weeds, and they were all cut to exactly the same length. The hedges were trimmed to perfect oblongs with rounded edges and there was no chewy on the paths. I knew he lived in there somewhere, in the rows of warm houses with big TVs, Marksies food, and lovely clothes. I wondered what he’d had for dinner: caviar and vegetables and fresh fruit for dessert. Definitely not a Fray Bentos.

I waited at the sign that curved around the mouth of Windermere Road, heard loud voices coming closer. Some of the older kids from school came out of Windermere, laughing like hyenas hunting for some carcass abandoned and left to rot. I lowered my head, turned my body slightly. Rob had already seen me. He was in my year, always out with the older kids.

‘What are you doin’ round ‘ere, ya little faggot?’ I’d never noticed before, but he had John’s eyes and mouth. His skin was pocked with acne scars, though.

‘Come ‘ed, lad, the game’s gonna start,’ one of his mates said.

‘I hate him though, lad,’ Rob said. ‘There’s somethin’ about him I just can’t stand.’

I stared.

‘Come ‘ed just leave it.’

They left. Rob looked back, but I could breathe again as all of my muscles untangled. My feet and fingers were freezing. I pulled my hands in through the sleeves and rested them across my stomach.

John stood across the street near the entrance to the farm. Had he seen the whole thing with his brother? My face burned red as I crossed over.

‘Here.’ He slipped gloves over my hands. They were massive; like the scarves Nan used to start knitting and forget to stop, wound round my neck loosely. ‘Come on.’

It wasn’t late, around six maybe, yet the streets were quiet. In the trees the hoot-hoot of an owl. We turned off the main street and onto the country lane that led up to a single house, veered left to cross a bridge, and wound through the countryside. I didn’t know the name of the road, who lived in that house, or what the bridge was called. I called it John’s Bridge after him.

My phone vibrated hard in my pocket. I fished it out, held it in both hands, stared into the shining green screen. In grey-black lettering a text from Vicky: ‘U OK?’

I pressed button 4 three times, 0 for space, 2 once, 6 once, 0 once, 3 three times, 4 three times, 6 twice, 3 twice.

‘Your mum?’

‘Vicky. Just checking up.’

‘She should just ring. I hate texting.’ He grimaced. ‘It’ll never catch on. Takes too long.’

‘Yeah, you’re right.’ I slipped the phone back into my pocket.

With the shush of some stream or river beneath us and convinced nobody would come by, he put his hand on the back of my head and kissed me. His other hand reached down for my bum and he pulled me closer. Not aggressively, but slowly. Softly. I wrapped my arms around his waist and found it spongy. Cushioned. I liked it. He was bigger than me, wider, taller, smarter, and my trousers got tighter. He wouldn’t be able to see.

His tongue was soft and tasted like Listerine. Under that, the faint persistence of a cigarette. I didn’t know he smoked. I liked him more. Drew him closer. The soft strums of The Sundays’ cover of Wild Horses reverberated in my mind. The part in season three where Buffy has her ‘perfect high school moment’ at the Prom. If we had a Prom would he take me? I’d wear something nice, but he’d look stunning in a black tuxedo and bowtie, his hair slicked back with copious amounts of blue sticky gel from a clear tub with a white label.

When we finally came up for air and sat on the cold concrete, he folded me into his coat to keep me warm.

He kissed my ear and I was beaming. I had butterflies in my chest that swooped like hungry bats. This must be what Buffy felt like when Angel held her. She wanted to be a normal girl as much as I wanted to be a normal boy. But I felt, like she did, maybe that was impossible in the worlds we lived in.

‘I’m not using you,’ he said.

‘I know.’ I said it without thinking. I didn’t need to think, was unable to, in those hours we spent together.

We held hands as we walked down the lane where nobody ever drove until we reached the main street, crossed over to the park. Parks at night time are eerie things. Like graveyards. Swings lifted and squeaked and even the roundabout turned like the wind was ghost children.

He stung his hand on some tall nettles which grew at the entrance. He hissed as he drew his hand closer to see. We sat on the swings straddle-style so we could face each other. They were wet with rain and I blew on his hand.

‘You know, I nearly lost this hand,’ he said.

I laughed. ‘It’s just a sting.’

‘No, I mean really.’ His eyes locked on mine. ‘I had a tumour.’

This was the moment where Buffy would say something sweet and say it softly, describe his hand as perfect then kiss it. Even touch it to her face. I turned away. My face burned despite the cold.

‘What happened?’ I asked, finally.

‘It was taken out,’ he said. ‘I’ve got this massive scar across my shoulder. Hate it. Felt like everyone would stare at me in school. Just used to come home and lose myself in books.’

‘That sounds lonely.’

‘I got used to it.’

That hung in the air between us, a sharp piece of ice on the bitter wind. I knew it needed to be thawed, but I didn’t know how.

The wind got stronger, the night colder, and he said, ‘You should get going. Bit of a walk back to yours.’

‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘I was just going to say that.’ I wasn’t. I never would. We kissed one last time at the corner before we turned out of the pitch park onto the lit road. He walked up his street with a spark and puff of smoke. With Temptation Waits by Garbage on repeat, I analysed everything we’d done and said. Which wasn’t much.

I’m not using you he’d said.

The next morning the school corridors were icy. The single-pane windows clattered like someone just come in from the cold. The old blue laminate tiles were ripped in parts and in others massive blisters had formed filled with air. My feet were heavy from the trek last night and my legs ached.

The music stopped dead in the middle of the Buffy/Angel love suite, Close Your Eyes just as each instrument clawed out a crescendo. The mp3 player’s screen flashed blue and faded to a bleak grey. Gutted.

The old building, the Molyneux was so quiet at this time of the day. As always, I was in before anyone else arrived. Not even Vicky got into school that early. From the quadrangle, filled with plants, trees, and animals, the gentle rolling trill of wood pigeons.

Footsteps ahead. Someone with squeaky shoes. It was John and he rounded the corner near the library doors. The notices and announcements loosely cellotaped to the frosted windows fluttered as he passed. His blazer fit perfectly over a green Adidas hoody. He looked bulky. Muscular. He scanned the corridor and me and chanced a smile. Nobody was around after all.

His pace quickened. The walk-sprint of he in a desperate hurry. In his hand was a square slip of paper scored with faint blue lines like veins. He passed and the paper was in my eager sweaty hands and it felt hot. A potato baked on one-hundred and twenty degrees, whose skin I couldn’t wait to crack and butter.

I tried the library doors, on which a notice for a missing green budgie belonging to Mr Brown of 47 Deyes Lane was stuck to. Mrs Jones mustn’t be in the library yet. The door to the cooking room was open and inside smelled like flour and sugar. I dragged a stool close to a work bench. There were names and dates and love hearts from relationships that had died before the end of the year scratched into the worktops with sharp pencils and compasses. I thought about our initials – mine and his – how they’d look in the faded varnish. They’d be too obvious.

I unfolded the creased paper and it smelled like his aftershave. I remembered it from that shop in St John’s Precinct. CK1 by Calvin Klein. It smelled clean, fresh, edible – like fruit salads in summer.

This was the first time I’d seen his handwriting, and it looked like my little sister’s. Massive looping lines and circles over each i and j instead of dots. I felt a pang of embarrassment for him, then for myself as I remembered last night. I know he might have struggled to write it, found it hard to grip the pen and form these words. But he’d taken the time to do it. Maybe every full-stop was a jab to his shoulder. Every time he wrote ‘and’ would feel like the blade of the scalpel bursting open his skin. He’d suffered in writing it but here it was.

He rambled a bit about how his mum had smelled smoke on him when he got home, asked where his gloves were. Before saying he’d written the note so I could throw it away, he moved on in more careful handwriting. Tighter. Smaller, somehow. He’d enjoyed seeing me last night, was sorry if what he’d said had made me feel weird.

‘It didn’t,’ I said to no one.

He wanted to see me that night if I could. I should send him a text message which, as always, would be blank save for a full-stop. I imagined him opening his phone to read it. My number wouldn’t be saved in the phone’s memory and the digits of my number would be grey lines on top of the small green screen.

I sent the full-stop straight away.

First class was German. I walked into class just as the scallies were turning the desks around to face the opposite way so when Mr Vandervelde came in he would be furious.

‘Oh ‘ere she is, lads,’ Rob said. ‘Watch your dicks, Sausage is about.’

I didn’t look at them, tried to ignore their laughing, and sat down near the front of the class, next to the window.

It was mildly funny to see Vandervelde burst in, arms flailing, spit sputtering from his lips. Furious about the desks. Laughing hysterically, Rob sat at the back, arms sprawled across an entire desk like an ape. Like his friends.

‘’ey sir, what’s German for ‘Sausage’.

‘Stop this!’ Vandervelde shouted.

One of the others flicked through their textbook. ‘Wurst, lad.’

‘Ich liebe Wurst.’ Rob laughed. That high pitched thing, like a train pulling into Lime Street.

My fingers curled into balls, nails dug into the palms of my hands. The shape of Buffy was coming through my skin. ‘Dein Bruder leibt Wurst.’

Vandervelde’s mouth fell open.

‘What did you say, you queer?’ Rob stood up.

‘I said your brother’s gay.’

He slammed his chest and spread his arms wide. ‘You wanna stand up and say that again, lad?’

‘It won’t make a difference if I stand up or sit down.’

‘He’s got a bird, you soft little wan-’

‘Get out! Get out!’ Vandervelde huddled Rob out of the room.

My palms were sweaty, my chest clenched hard and I could hardly breathe. I sat there when class ended, stared out of the window at the sunny day. My breath formed imperfect foggy circles on the glass widening and dissipating with each exhalation.

Two magpies hopped about the glass outside, squawked and rattled and tossed the lifeless, messy carcass of Mr Brown’s budgie between each other.

I ate my beans on toast quickly, felt it swish in my stomach as I jogged to make up the twenty minutes lost while my brother was in the bath. I played a CD I’d burned from disc to my computer, Sarah McLachlan’s Surfacing album. I played Full of Grace on repeat from the episode where Buffy had to kill Angel to save the world.

There were no clouds. The odd star shone behind the glare of lanky lampposts. I made my way down through the estate, along the country lane, onto the corner where the path to John’s Bridge met the main street. There was nobody here.

Eventually the clouds shrouded the sky, covered the constellations. I was getting colder just stood there. I lifted my feet in succession and rubbed my hands together. My bones were beginning to feel the cold now, too. It was eight o’clock and there I stood.

I text him another full-stop and waited. And waited. I took off his massive gloves and left them on the corner to our path about quarter past eight and headed around to Vicky’s.

‘What’s wrong?’ She pulled me inside straight away. Her house smelled like stewed meat, but not nice. Like it hung in the air from days ago. ‘What’s he done to you?’

I couldn’t speak. I tried but between sobs it made no sense.

Vicky rang a taxi for me, took a fiver from an empty bottle of whiskey she kept next to the bulb-lit fire inside a fake marble surround. My mum had the same one.

‘I’ll walk.’ I stood up, felt the bare bones of the couch under my hand as I rose and walked the floor.

I made the journey home about nine. Listened to It Doesn’t Matter by Alison Krauss & Union Station and thought my tears would freeze in the cold. It was six miles home. I walked there.