Author note: If you’ve ever lost someone you loved, you’ll know how painful it can be; how even thinking about them can bring tears to your eyes.

When I was in my first year at university, I lost three of my grandparents within the space of nine months. I thought about giving up my degree, but knew none of my grandparents would want me to.

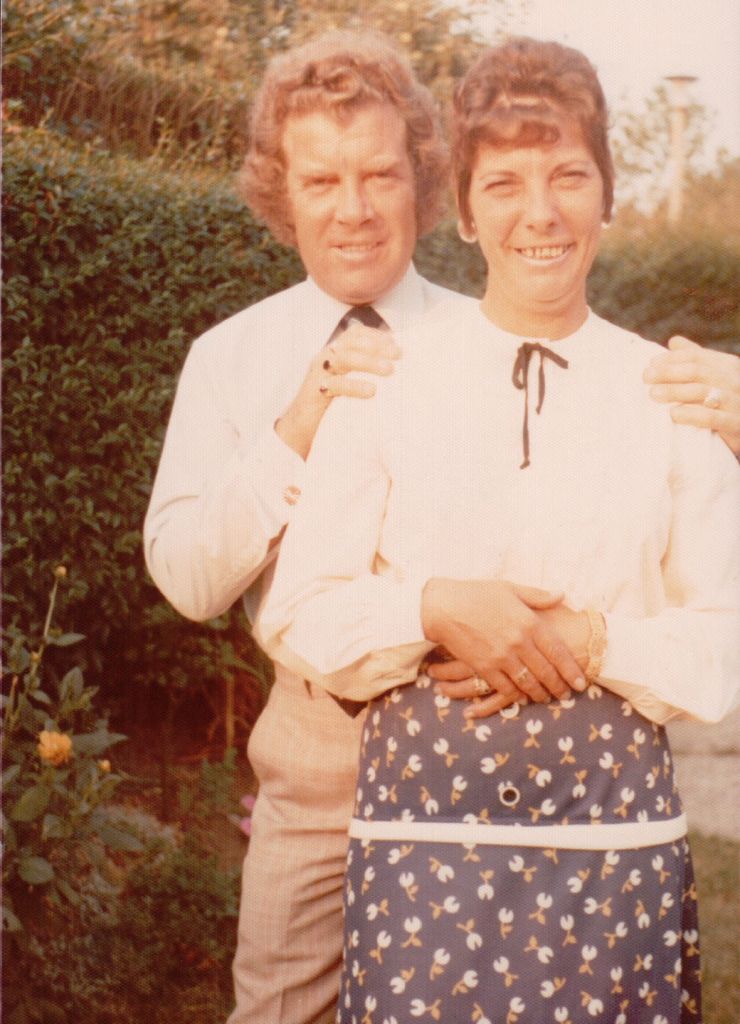

“Newquay and The Seekers” is a short story about two of my grandparents, Winnie and Jim Watkin. Most of the events of the story are factual, but some things have been changed. An earlier version of this story was published as “He’s Gone” in the Fresher Writing Prize 2015 collection.

Newquay and The Seekers

‘I’ll be alright,’ you’d said, ‘don’t mither.’ You took the old rusting case of tools and nails upstairs in the boots you used to wear for work, the ones where the leather had worn away exposing the steel toe-cap underneath. You laughed when I wrapped a cheddar and sweet pickle sandwich up in a piece of tin foil and said, ‘Just like the old days, ‘ey love. I do miss ‘em.’

‘Just like the old days,’ I agreed as I flicked on the kettle to boil. We didn’t know it then, in that moment in the kitchen where we longed for the years that had slipped us by, that we would mull over that interaction. We would analyse it silently, and it would become a juncture of many possibilities. Many, many what-ifs. There was more to say, there always is when you part company with someone you love, even if they are only going upstairs.

The toolbox rattled against your calf as you lumbered away to the stairs. The dog yelped, the tiny screech that put your teeth on edge, and you said, ‘Bloody hell, Wendy! Mind out the road.’ That was the last time I heard you speak.

I’d been on at you for months about converting the loft into an extra bedroom for the grandkids. I imagined we’d get someone in to do it, or ask our John for help, but you wouldn’t, you proud bloody fool. You were years past retirement for God’s sake! We both were. ‘I’ve been building things with these two hands for decades, I’ll be damned if I stop now,’ you’d said.

‘Oh, your arse in parsley, Jim!’

You hammered for hours, while I played PlayStation, and in the afternoon I browsed brochures of white-painted houses in Newquay. Right there on the seafront, basking in the glorious sunlight. It could easily have been somewhere abroad; it looked so lovely. I’d dog-eared the pages I wanted you to see and left them on bottom stair, the houses that were in our price range; I’d show you later on before Law and Order: Special Victims Unit.

We’d always dreamed of moving down there, ever since our first camping trip with the kids in the 1960s. The tent had been brown and orange and smelled like gardening gloves, and you always said it looked like the blouse I wore the first time we went out. We would pitch the tent and sit with other families around a spitting fire, someone played the guitar and we all sang The Seekers, the one where they sang about having a world of their own, and we dreamt of a house in Newquay.

The hammering stopped sometime during Tony Snell’s radio programme. I was making you another cuppa to bring up to you, and I remember the steam wheeled out of the spout and rested on my glasses, and as I chuckled to myself, I heard you. Like a moan and a roar at once, and I wasn’t sure if it sounded like my name or not. It was unreal. Unnatural. Agonised.

I bounded up the stairs, steaming tea in my hand, as you thumped down the loft ladder onto the landing, a small square connecting three bedrooms.

You gripped your head in trembling, waxy hands, and your face was shades of pink, do you remember? You’d never looked so frightened. Spittle flew from your mouth and your screams lagged into a groan, like when you slow a record to 45. You looked then like you do right now: your lips and chin trembled, you stared but didn’t see – you looked behind me, beyond me, and saw something else I think.

I put the mug down by the side of the stairs and raced for the phone in our bedroom, dialled the emergency number and sank to my knees next to you. I knocked the tea down the stairs, heard the mug crack at the bottom and Wendy barked and thumped at the living room door. She wanted to be there by your side too. I held you close, tried to keep your shivering body still.

You became quiet, laid still, your eyes closed and I remember holding my breath. You looked like you were sleeping, and I hoped that you’d wake up, when the doorbell rang. I had to leave you there on the landing on your own and dodge the broken mess of tea and mug, which had soaked into the magazines, causing them to curl.

They asked your name, the ambulance men as they flew up the stairs before me. ‘Jim,’ I said. ‘James.’ They didn’t look at me, but lifted your arms and watched them drop to your side with a heavy thud. ‘He’s my husband.’

You were carried out on a stretcher to the ambulance waiting at the bottom of the drive, its blue lights washing over the red brick houses. The neighbours were all out in their yards, I could see their faces and hear them asking questions, but all I could think of was that I was out of the house in those pink bloody slippers you bought me for Valentine’s Day. As the ambulance pulled away from Kemsley Road, I realised I’d forgotten to lock the front door or let Wendy out for a wee, and I wasn’t entirely sure whether I’d saved the game I was playing.

**

You were disappeared on a wheeled bed through two automatic doors, which swished as they closed, while I was left to wait because I couldn’t come with you. The hospital was cold and the damp lino smelled like disinfectant, and I remember the plastic chairs, bolted to the floor, weren’t very comfortable.

The last time I was sat in a place like this was ten years ago, when I thought I would lose you then, too. I’d been on at you to improve your diet – to eat more fresh vegetables and fruit, but you always knew better. ‘Something’s got to lead you to Jesus,’ you’d say, ‘and I’d rather go with a belly full of bacon and ale than with a sack full of sunflower seeds.’

‘I doubt Jesus would appreciate you stinking of bacon, Jim,’ I’d said.

‘You telling me he wasn’t partial to a bacon butty? Don’t make me laugh, love. He didn’t have much in life, but I’m sure he didn’t deny himself of that.’

‘He was Jewish.’

The payphone receiver was warm and sticky and my 10p was returned to me five times before I slid a pound into the slot. That seemed to work. ‘Hello John, love,’ I said. ‘Listen, your dad’s in hospital.’

‘What’s happened?’

I didn’t know how to answer because I didn’t actually know. The words caught in my throat, it swelled with them. ‘Could you go to the house? I think the front door’s unlocked. Let Wendy out for a wee, and make sure she’s had some food and has water.’

‘Mum!’ His voice cracked. ‘Which hospital are you in?’

A doctor came out and looked around until he saw me. ‘Ring Peter. I’ll have to go. Oh, and put the heating on low love,’ I told him. ‘Your dad’ll like it to be warm when he gets home.’ I put the phone down.

The doctor approached me. ‘Mrs Jackson?’ He wasn’t from around here. Southern, I think. He took my arm gently and showed me to a seat. He introduced himself. One of those names you’d never remember how to say, you know; like some Greek island. ‘Was that your family you were on the phone to?’

‘Yes, love,’ I said. ‘My sons will be coming soon.’

His eyebrows bunched over wide brown eyes and he locked his fingers together on his lap. ‘That’s good,’ he said finally, looking away. ‘Your husband has had a haemorrhagic stroke, Mrs Jackson. I’m sorry, but I have to prepare you for ––’

I stopped listening. I heard him talk about you in whispers, discreetly, as though you were in the grey corridor with us. He spoke as if you were going, as if you were already slipping away. I listened to him drone on, as if I was under water and all I could hear were mumbles. He stopped and I recognised my name on the movement of his lips.

I had to speak now. My turn. ‘So when can I take him home?’

‘Mrs Jackson,’ he sighed. ‘Perhaps you’d like to see him. Maybe you’ll understand what I’m trying to ––’

‘You don’t understand, my love,’ I said with a smile. I put my hand on his shoulder and squeezed gently, friendly. ‘He’s retired now, and we’re going to Newquay next week to look at buying a house. They call it your golden years I think, don’t they?’

He stood up, took my hand and led me toward those bloody doors. Beyond them, the scent of lemony floor cleaner gave way to something rich, warm and thick; the smell of anywhere dying people are.

A mask covered your face, wheezed oxygen into your mouth and nose, and tubes stuck into your veins. Your grey-blue eyes bulged out of their sockets, and your lips were cracked and dry. The doctor pulled a chair up beside your bed and left us alone, but I stood and watched you breathing and blinking, but that was all. ‘Bloody hell, Jim.’ I took your cold hand in mine, tried to warm it.

Everyone who visited you would say how lucky we were that you were still with us. But to me, there was nothing lucky about our new situation. You were you still you, but there was something missing, like that day greedily snatched away a piece of you.

The grandkids came every night, but it was hard for them to know what to say. They were just kids. You lay in that bed, mouth sloped to the left, your breath clattering in your wasting chest. They began feeding you through a tube in your stomach, and it was decided that you would come home to me. In the time you spent at home, our marriage defined a new meaning of intimacy, but we struggled through those few years, didn’t we love? I mean, we did our best.

**

I said I needed help, eventually. I remember the day so clearly. It was the first day I began to give up on things. You were playing your country records, Box Car Willie, I think, and I was playing the new Tomb Raider. You’d got up to go the loo and managed to slip on the runner in the kitchen, and I couldn’t get you up. I’d slipped too and fell on top of you. I scrambled to my feet, my shoulder sore and aching, and managed to get you upright. Your knuckles turned white as you held onto your Zimmer, and we hobbled together the final few feet to your chair.

When you were settled and our breathing returned to its usual slow pace, I checked you over. ‘Are you okay, love?’

You put both thumbs up, your ‘yes’.

I sat down on my own chair, and Wendy jumped up onto my lap. My shoulder throbbed, I rubbed at it and looked across at you. Your record finished, ready to be turned to the other side, and the room was quiet. The clock ticked on, resonant tuts, and the fire crackled between us. You lifted your good hand and pointed to your eyes.

‘What’s wrong?’

You pointed at me.

I had hoped you didn’t see. ‘I’m not coping well, Jim,’ I said. ‘I don’t think I can cope by myself anymore.’

You were silent, watching, and I saw wet slip down your face then too. Like rain on a window.

‘I’m not young any more,’ I said. I knew you could see the tears were still coming. ‘I’m tired. I think we need help, don’t we love?’

One thumb up.

**

They sent you to a home eventually, not your home, but a place of residence. It smelled like steamed vegetables and gravy, but the staff were happy enough. I showed them how to thicken your drinks in your favourite cup, so you could swallow without choking.

‘I’m trained, Mrs Jackson,’ one nurse said. ‘I know how to thicken a drink.’

‘You don’t know how I do it, love.’

The kids brought the grandkids every weekend to see you, and I came every day in any weather. Sometimes I’d bring Wendy. The other residents loved that, but she didn’t like the smell either and sat on your lap and panted her thick, wet tongue. God, she always shy wasn’t she, Jim? Always had to be near you, right on the arm of your chair.

It was hard for the grandkids to see you. To them you were the one who took them for walks up Rivington Pike and Moel Famau; the man who was building them a bedroom with his own two hands, the one who put them on his shoulders at the firework display. Now to see you sitting in that chair, unmoving, your mouth sloped and your breath rattling… well, it must have been hard on them.

That last winter was a furious one, can you remember? Snow came, thick and sparkling, like a blanket knitted from glitter wool. It was trampled into the pavement and turned roads and paths into cold, foggy glass. I couldn’t get to you. John and Peter had to wait for the ice to be dredged and turned to grey sludge at the side of the roads.

Every morning that winter, Wendy had me up early, before the birds even began to sing. She thumped at that living room door, howled like a hungry wolf until I came down to lie with her on the couch under a fraying blanket. She was missing you, I knew that. I was too, so I didn’t begrudge her the company. I never thought to turn on the heating, I was too tired to think straight.

It was the morning of the 20th of December. I’d let her out to do her business while I put the kettle on for coffee. I was already dressed, took the pipe cleaners out of my hair and brushed it, war paint on, ready to come and visit you. Truth be told, I felt exhausted, pain rang through my chest, and my body felt like lead. I didn’t want to leave the couch, but I couldn’t let you down.

I shuffled out into the yard in those pink bloody slippers. ‘Wendy,’ I called, then whistled her. ‘Come on now.’ I slipped on the last remains of ice and caught my shoulder and hip on the concrete step. I don’t remember screaming or making a sound. Shock, I suppose. I remember hearing the kettle boiling and Wendy barking, and then the quiet black.

**

The blue-haired crone in the bed next to mine sucked her Murray Mints far too loudly, like the sound the plug hole makes when you let the water out the bath. Somewhere, a radio was playing softly, and I wished they’d turn it up. I told Peter to close the curtains so at least I didn’t have to look at her. The hospital bed was comfortable, but it wasn’t my own, and I sank into the pillows as John told me what the doctor had said.

‘It’s a broken shoulder and hip,’ he said, stone-faced, ‘and severe pneumonia.’

I didn’t tell them about Wendy and the heating, I kept that to myself.

When the boys left, I thought of you in your bed, warm and listening to the kids tell you why I couldn’t come to visit. Just listening. I thought of what you had been through – so near to death you somehow found the strength to come back from it, to us. Sometimes, I thought, there’s strength, too, in knowing when to let it all go. That was the second day I gave up on things.

I was so happy when The Seekers came on that radio, and for those few moments before I slept, it was all I could hear. It was that sad one you loved so much, the one I’d come to like, where she’s asking him to walk with him through the night, and how he fills her world with light even though she’s lost and alone.

I fell asleep before the song ended, before the sun set, and I felt the room turn snug, the voices around me faded, the music seemed to echo softly somewhere, and I worried about nothing. It felt so easy, like exhaling – not an action we think about, but some function of the body that lays quiet, deathlike, until its moment comes.

Now, in the quiet of your room, I sit by your bedside and I hear your voice for the first time in years. It has called to me, and I came. You asked me to walk with you, and I will.

Your breath is ragged and your eyes sweep the room for someone’s hand to hold. You can’t feel mine on yours, but I am here. I know you don’t want to be here, I can see it in those grey waterlogged eyes. They’re telling me you want to go, that you’d love to be anywhere but here. I’m sorry, but there’s nothing I can do but wait for you. Wait and watch.

My hands are tied.

Breathe out and don’t draw it back; close your eyes, love, and remember that week we spent in Newquay after we were married. I suppose that’s why we wanted to go back. Because it had meant so much to us. Fresh from the chapel, laughing and drinking in the coastal sun with family and friends. Before the boys came along, before school runs, before worrying about redundancies at Fords and how we’d manage to put food on the table. The sun made the sand hot between our toes, and we went to sleep that night with salt in our hair.

It was just us two.

Close your eyes and remember that sun, the sand.

Remember the love we felt then, the love we carried with us through those tough years, into our golden ones.

Remember Newquay and The Seekers.